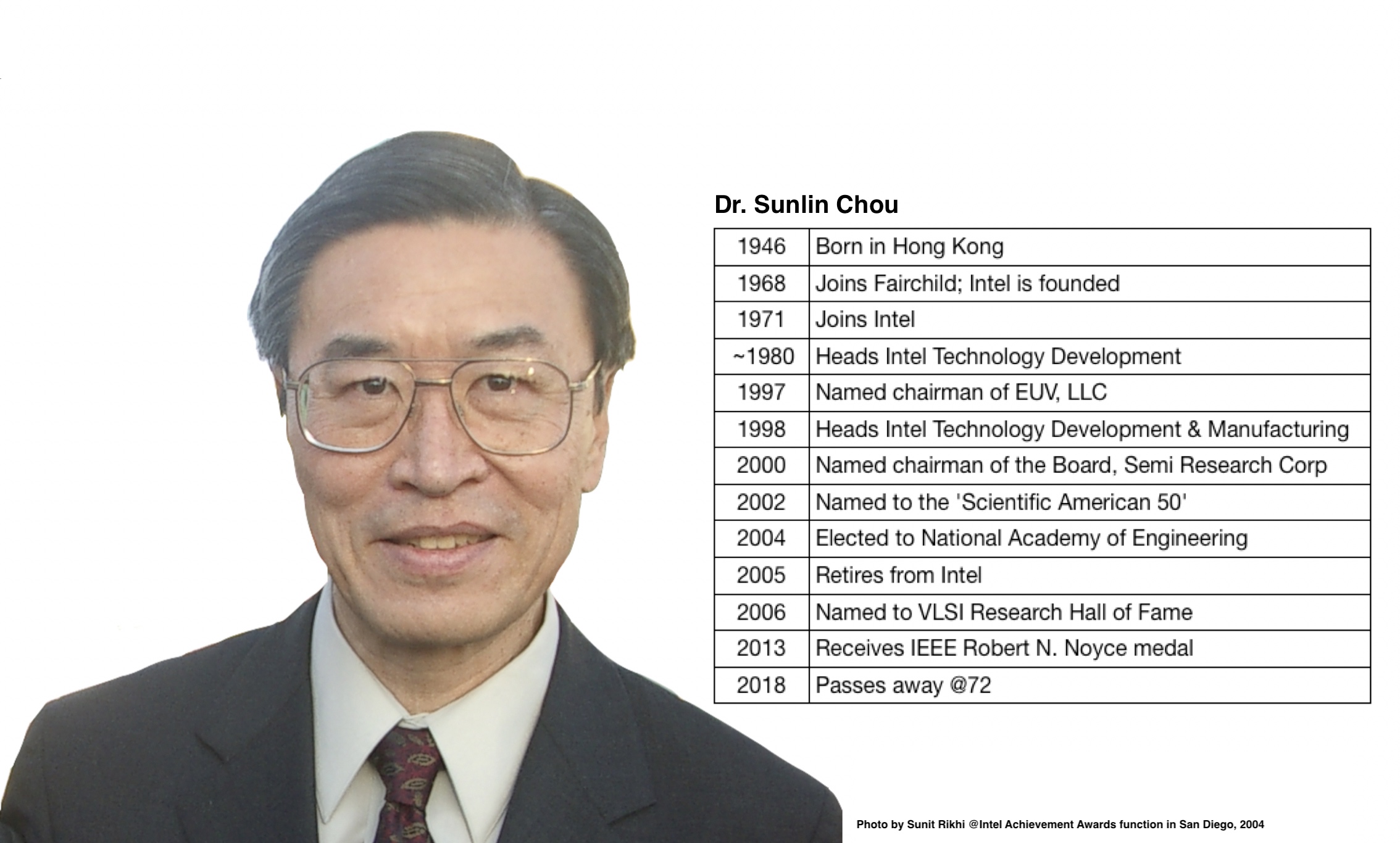

Sometimes we get to see, up close, leaders who make a truly enormous contribution to society. Dr. Sunlin Chou was one such leader and I was a fortunate fellow traveler. Sunlin led the exponential rise of transistors for 35 years, accelerating the waves of revolutionary digital technologies serving humanity.

Fifty years have passed since Sunlin entered the electronics industry in 1968. At that time, the industry was adding about 1 transistor every year to the service of every human on earth. By the end of Sunlin’s career in 2005, the industry was giving 7 billion transistors every year to each of us. Today, you and I are receiving well over 50 billion transistors each.

Do you know where all of yours are? I don’t either, but I know that my transistors live just about everywhere. They wiggle on and off at speeds unimaginable, to support my everyday needs.

Sunlin had the fortune of joining this transistor exponential in its infancy. The exponential is made up of waves of transistor manufacturing technologies, each bigger, better and steeper than the previous wave. Bigger, because each wave made exponentially more transistors than the previous wave. Better, because we made each transistor faster, less power hungry and half the size compared to its predecessor. And steeper, because we ramped the production of transistors faster than we did in the previous wave. If a wave was not bigger, better, steeper and on time, there was a stiff economic penalty to be paid.

How do you ride such exponential waves consistently and elegantly over decades?

The answer is found in the architecture and disciplined use of an organizational machine Sunlin invented. The purpose of the machine was to synchronize the aspiration, the energies and the output of thousands of people riding the wave from across the globe and, over several years. The result was one spectacular exponential wave after another, of transistors penetrating our lives at ever increasing rates.

Sunlin’s synchronizing machine was as simple as it was impactful. At its very core was the concept of synchronizing (synch) points. These were well-defined and well-marked stakes in the ground which had to be reached predictably. Sunlin chose the manufacturing ramp of every wave as its master synch point and he mandated its placement on a 2-year cycle between waves (2-year rhythm maximizes the economic value of riding transistor waves). All activity across Intel and the semiconductor ecosystem was pipelined to synchronize at that synch point.

A key architectural feature of Sunlin’s machine was the partitioning of the multi-year pipeline into Research, Development and Manufacturing (RDM) phases. The Research phase pruned technology options to carry forward into Development. The Development phase defined the new wave’s specifications and developed manufacturable ICs made up of transistors. And the Manufacturing phase ramped and maintained transistor production for the rest of the wave’s life. Each phase was well defined in terms of deliverables and hand-off points which served as intermediate synch points in the pipeline.

The structural integrity of the machine was in the disciplined use of built-in risk management features.

An example is Sunlin’s “COPY EXACTLY!” (“CE!”) doctrine. In the manufacturing phase of the pipeline, multiple factories were needed to support the manufacturing volumes of transistors in a wave. Sunlin programmed the machine to replicate technologies in each fab, one after the other, in order to ensure an un-interrupted flow of increasing output during, and after, the rise of the wave. So detailed were the copy spreadsheets, and so strong was the intent to copy exactly, that we never used the phrase “CE!” without the exclamation point.

As a second example, Sunlin designed large overlaps in the transitions from R to D and D to M in the RDM pipeline. At these transitions, some wave riders stepped off and others stepped on to take the pipeline further. To ensure un-interrupted flow of work through these handoff points, Sunlin sent developers upstream to work with researchers to finish, and select, research streams for the development phase. He sent developers into the manufacturing phase by making them responsible for the first manufacturing ramp of the wave. And, he sent manufacturers to work alongside developers to learn, finish and copy the technology for subsequent factory ramps of the wave.

Yet another example is the way Sunlin limited variables in the development phase of the RDM pipeline. Manufacturing technology in a wave was expected to re-use more than 80% of the equipment of the prior wave. This change control limited exposure. He also imposed a restriction on the design of the chip leading the wave. It was expected to reuse the architecture from the prior generation with changes limited to those required for manufacturing. This controlled the risk that came from debugging simultaneous changes in design and manufacturing of the chip leading the wave.

A networked hierarchy of synch meetings served as the synchronizing machine’s operating system. These meetings included multiple cross-functional engineers who followed time tested dashboards to keep the wave’s relevant synch points front and center. Sunlin attended the highest synchronization meetings on a regular basis. One of them was a bi-annual meet where he interacted with hundreds of senior engineers representing hundreds of organizations and disciplines, gathered to take a holistic view of the wave.

When Sunlin passed on in December 2018, there was an outpouring of sentiment from those whose lives he had touched: “a brilliant mind”, “a well-balanced man”, “a gentle soul”, “a humble man”, “grounded in competence”, “integrity and class”, “an authentic, empathetic manager”, “a pioneer”, “a conceptual thinker”, “an inspiration to all”, and “a legend!”.

Sunlin was all that and more. Sunlin exemplified the power of architectural integrity in conceptual thinking. He showed us how it can serve as a solid foundation for journeys unimaginable.